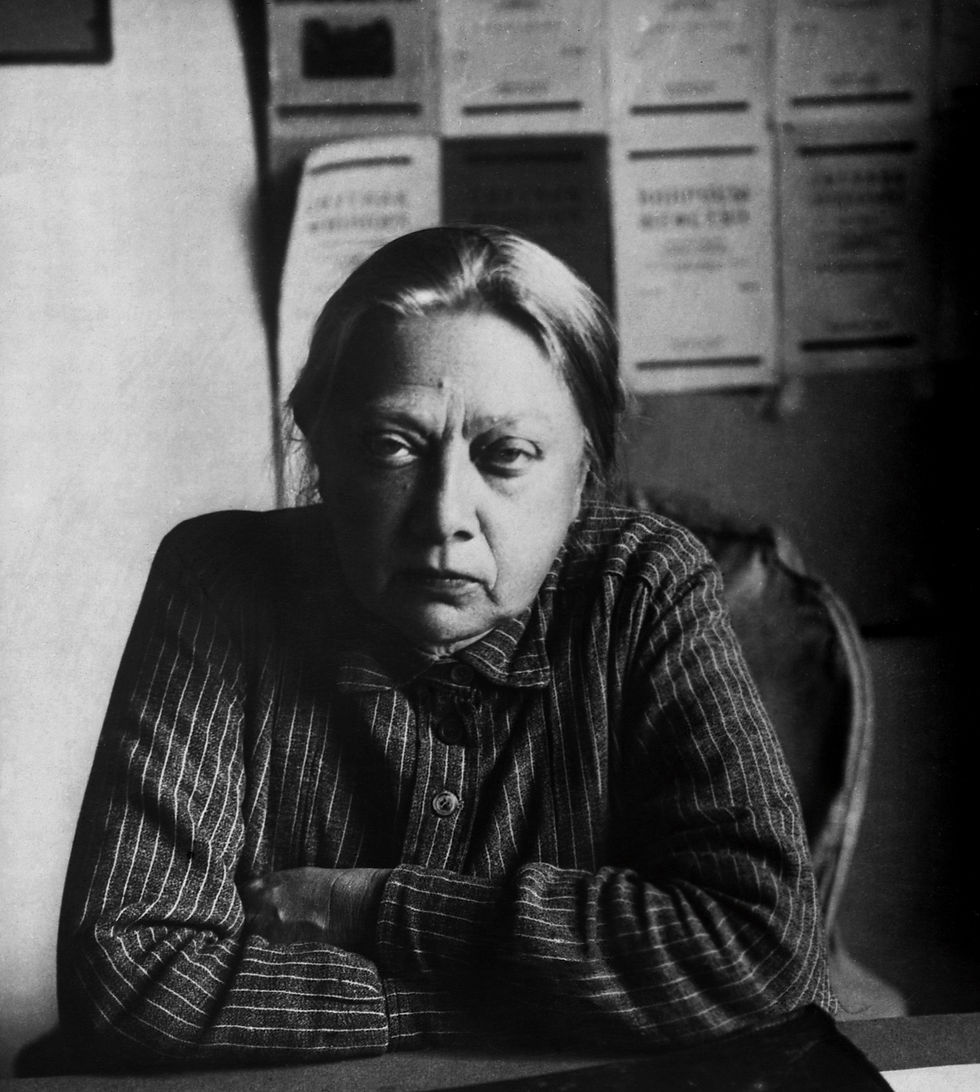

Nadezhda Krupskaya, b. February 26, 1869

- Michael Laxer

- Feb 26, 2022

- 5 min read

"I am very happy that I experienced the revolution. I love the work I am doing. I had a wonderful personal life. If I were to begin life all over again. there is little I should want to change." -- Nadezhda Krupskaya

The great Bolshevik revolutionary Nadezhda Krupskaya was born February 26, 1869. She died February 27, 1939.

Here we pay tribute to her and her exceptional work both before and after the revolution with a Soviet article about her from 1967.

Text (exceprted):

IN A TWO-HORSE CART rolling along a country road sat a young woman with a thick braid of light brown hair. She carefully held a kerosene lamp with a green glass shade and a bundle of books in her lap. An elderly gendarme lolled beside her. He was escorting the young woman to the Siberian village of Shushenskoye. From her documents he knew that she was going to that godforsaken place of her own accord.

"You should have chosen Ufa," the gendarme told her. "You'd find life easier in a town. You're young. You'll grow old fast in Shushenskoye."

"My fiancé is in Shushenskoye."

"What a fiancé!" The gendarme shook his head. "He's driven you to Siberia before he even married you."

The woman was Nadezhda Krupskaya. The judicial investigation had established that she was a member of the secret League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class that Vladimir Lenin had founded in 1895. For that the court sentenced her to three years' exile in Siberia, in the town of Ufa. But she asked to be sent to Shushenskoye, a place still farther away where conditions were even harder, because that was where Lenin was living in exile.

The marriage took place on July 10, 1898, in the tiny Shushenskoye church. A difficulty arose: the bride and groom had no rings. A fellow exile, a St. Petersburg worker named Oscar Enherg, came to the rescue. Out of copper coins he fashioned two rings that shone like gold. Nadezhda Krupskaya treasured them all her life..

Nadezhda Krupskaya was secretary of Iskra, the leading Marxist illegal newspaper, and also secretary of the Central Committee of the Party. After the revolution she directed the campaign to end illiteracy. Three-fourths of the 170 million people in Russia were completely illiterate. She set up a system of courses and study groups in factories, in rural areas and on construction sites, and drew in tens of thousands of intellectuals as teachers. The goal of universal literacy was reached in an incredibly short time. The achievements of socialism would have been impossible without this cultural revolution in which Nadezhda Krupskaya was a guiding spirit.

The young people who worked at the People's Commissariat of Education marveled at her energy and capacity for work. One of her close friends. Fyodor Petrov, recalls:

"Late one evening, as I was passing the Commissariat, I saw lights in the window of her office. I dropped in. Nadezhda Krupskaya was seated at her desk editing a manuscript. She looked tired, there were circles under her eyes and her skin was sallow. She looked at me over the top of her glasses and motioned me to a seat. The telephone rang. It was Lenin asking why she was working so late. The doctors had forbidden her to work so hard, he said. "They also forbade you to," she told him.

Lenin must have said he was already home. She promised to be home soon. Then she hung up the receiver. "I'm sure he's still working," she said with a smile. "The call came from the Council of People's Commissars. The phone there has such a hollow sound I can always tell it from our phone at home. But that will never do. He shouldn't be working so late."

She was always concerned for Lenin. During his long illness that began in 1922 she remained "heroically calm." in the words of the same Petrov, as she saw him fade away before her eyes. That January day in 1924 when factory and train whistles blew all over the country must have been the first time in her life she did not conceal her grief. She no longer had anyone from whom to hide her pain. Lenin was dead.

She buried her anguish in work. Nadezhda Krupskaya worked hard. Even when she was already old she wrote to friends: "There is so much to be done. I'm getting on in years and I suppose I should try to take it easier, but I can't."

Her secretary kept a list of her writing and speeches in the course of a single month-20 articles on education, 16 speeches, and 240 letters!

She was popular in the country both as Lenin's wife and in her own right as Deputy Chairman of the People's Commissariat of Education. She received as many as 500 letters a day and answered most of them. Many came from children. Some made her happy, others saddened her, and still others left her with mixed feelings.

Take this one. "My name is Pavel Koposov. I am writing this letter not from joy but from sorrow. Our leaders tell us that we, the younger generation, will be their successors. These successors must be strong people to carry on their work. But not all of us are strong, because we don't all get the same food. Those who live under good conditions can become successors. But I won't be any good as a successor because of the way I have lived ever since I was small. I used to think I ought to cut my throat, or take to stealing. But I got over that. I know it would be a disgrace to the whole country if I stole. The conditions I am living under now are very bad, and there are other children in the same position. That it why not all of us can be successors to those who are now fighting for the working class."

A reply went out almost immediately to the out-of-the-way village in Kirovsk Region.

"Dear Pavel," Nadezhda Krupskaya wrote. "1 am glad to know that you think of other children as well as yourself. I am glad that you have learned how to overcome bad thoughts. I have shown your letter to some of the comrades and asked them to make sure that the children of Kirovsk Region get better living conditions. You did right to send me a letter. I can see that you have a good mind, although you do not write very well."

Then followed detailed advice on how to learn to write without mistakes.

Nadezhda Krupskaya told the regional department of education, the Children's Commission of the Central Committee and the highest legislative body in the country about the letter. She did not lose sight of the boy, and two years later was able to have him admitted to a model boarding school. "I believe," she said in her letter to the director of the school, "that this boy will grow up to be a fine citizen."

Eighteen year old Pavel Koposov volunteered for the front in 1941 and was killed in battle near Smolensk. He wrote to his adopted mother regularly to the day she died.

In the story of her life. which Nadezhda Krupskaya wrote especially for schoolchildren, she said: "I was always sorry that I had no children myself. Now I am not sorry, because all of you are my children."

One Sunday at the end of February 1939, Nadezhda Krupskaya decided to celebrate her seventieth birthday by spending the day at a holiday house near Moscow. But instead of a celebration there was grief, for that evening Nadezhda Krupskaya collapsed.

She regained consciousness only the next day. "Am I ill?" she asked the doctors, peering at them with her shortsighted eyes.

She was buried in the Kremlin wall beside Lenin's Mausoleum.

コメント