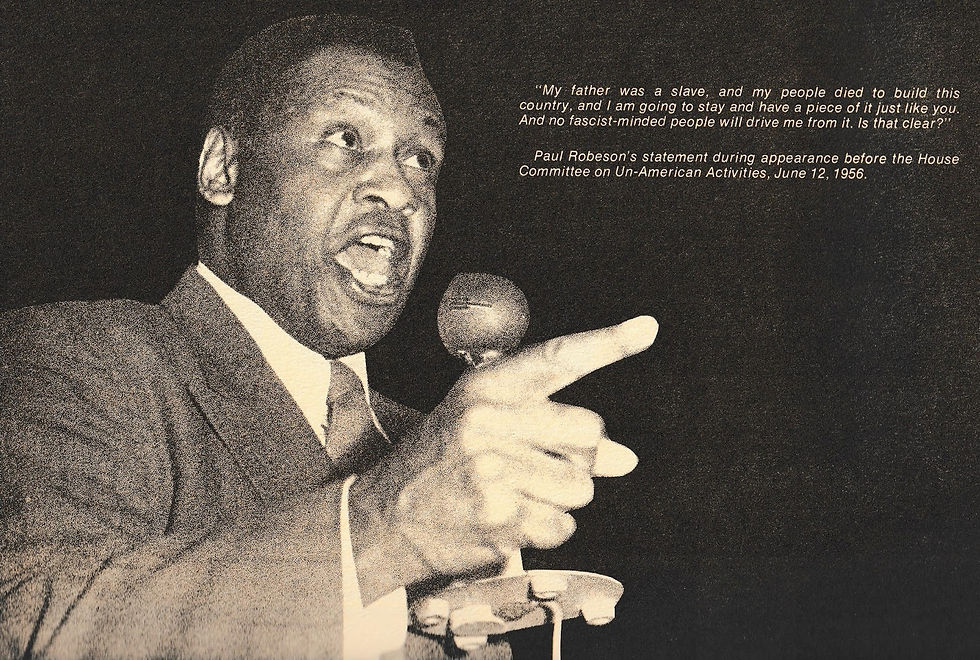

On June 12, 1956 the great American singer, actor, athlete, Communist and all-around Renaissance man Paul Robeson appeared before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) and with tremendous courage stood up to those who questioned him as part of this terrible McCarthyite witch hunt.

With the rise of the Cold War and McCarthyism, as was noted in a previous post about Robeson, in 1950 Paul Robeson's passport was revoked by the State Department. An unprecedented executive order signed by President Truman forbade Robeson to set foot outside the limits of the continental United States on penalty of five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. The government made it plain that a boycott was to be imposed on Robeson: no concert hall. public or private, would rent to him, and the mass media were closed to him. But he continued to sing and speak across the country in the churches of the Black communities and in union halls.

In 1956 during his appearance before HUAC he was grilled by Richard Arens (counsel for HUAC and a former aide to Senator McCarthy) and bigoted Committee members such as Gordon H. Scherer and Chairman Francis E. Walter, but not only stood his ground he defiantly faced them down with such comments as "you are the un-Americans, and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves."

In one incredibly stirring moment when asked why he did not "stay in Russia" he answered "Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no Fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?"

Robeson would break through the ban against his performances in 1957 in Oakland, California with a triumphal series of appearances, including a standing-room only concert in the municipal auditorium.

His passport was finally reinstated in 1958 by a supreme court ruling after a campaign by -"Committees to Restore Paul Robeson's Passport" that sprang up in the U.S. and around the world.

Today in honour of this act of courage by this great man we republish in full his testimony before HUAC as well as the statement he had prepared to read to the committee but was never allowed to.

THE CHAIRMAN: The Committee will be in order. This morning the Committee resumes its series of hearings on the vital issue of the use of American passports as travel documents in furtherance of the objectives of the Communist conspiracy. . . .

Mr. ARENS: Now, during the course of the process in which you were applying for this passport, in July of 1954, were you requested to submit a non-Communist affidavit?

Mr. ROBESON: We had a long discussion—with my counsel, who is in the room, Mr. [Leonard B.] Boudin—with the State Department, about just such an affidavit and I was very precise not only in the application but with the State Department, headed by Mr. Henderson and Mr. McLeod, that under no conditions would I think of signing any such affidavit, that it is a complete contradiction of the rights of American citizens.

Mr. ARENS: Did you comply with the requests?

Mr. ROBESON: I certainly did not and I will not.

Mr. ARENS: Are you now a member of the Communist Party?

Mr. ROBESON: Oh please, please, please.

Mr. SCHERER: Please answer, will you, Mr. Robeson?

Mr. ROBESON: What is the Communist Party? What do you mean by that?

Mr. SCHERER: I ask that you direct the witness to answer the question.

Mr. ROBESON: What do you mean by the Communist Party? As far as I know it is a legal party like the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. Do you mean a party of people who have sacrificed for my people, and for all Americans and workers, that they can live in dignity? Do you mean that party?

Mr. ARENS: Are you now a member of the Communist Party?

Mr. ROBESON: Would you like to come to the ballot box when I vote and take out the ballot and see?

Mr. ARENS: Mr. Chairman, I respectfully suggest that the witness be ordered and directed to answer that question.

THE CHAIRMAN: You are directed to answer the question.

(The witness consulted with his counsel.)

Mr. ROBESON: I stand upon the Fifth Amendment of the American Constitution.

Mr. ARENS: Do you mean you invoke the Fifth Amendment?

Mr. ROBESON: I invoke the Fifth Amendment.

Mr. ARENS: Do you honestly apprehend that if you told this Committee truthfully—

Mr. ROBESON: I have no desire to consider anything. I invoke the Fifth Amendment, and it is none of your business what I would like to do, and I invoke the Fifth Amendment. And forget it.

THE CHAIRMAN: You are directed to answer that question.

MR, ROBESON: I invoke the Fifth Amendment, and so I am answering it, am I not?

Mr. ARENS: I respectfully suggest the witness be ordered and directed to answer the question as to whether or not he honestly apprehends, that if he gave us a truthful answer to this last principal question, he would be supplying information which might be used against him in a criminal proceeding.

(The witness consulted with his counsel.)

THE CHAIRMAN: You are directed to answer that question, Mr. Robeson.

Mr. ROBESON: Gentlemen, in the first place, wherever I have been in the world, Scandinavia, England, and many places, the first to die in the struggle against Fascism were the Communists and I laid many wreaths upon graves of Communists. It is not criminal, and the Fifth Amendment has nothing to do with criminality. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Warren, has been very clear on that in many speeches, that the Fifth Amendment does not have anything to do with the inference of criminality. I invoke the Fifth Amendment.

Mr. ARENS: Have you ever been known under the name of “John Thomas”?

Mr. ROBESON: Oh, please, does somebody here want—are you suggesting—do you want me to be put up for perjury some place? “John Thomas”! My name is Paul Robeson, and anything I have to say, or stand for, I have said in public all over the world, and that is why I am here today.

Mr. SCHERER: I ask that you direct the witness to answer the question. He is making a speech.

Mr. FRIEDMAN: Excuse me, Mr. Arens, may we have the photographers take their pictures, and then desist, because it is rather nerve-racking for them to be there.

THE CHAIRMAN: They will take the pictures.

Mr. ROBESON: I am used to it and I have been in moving pictures. Do you want me to pose for it good? Do you want me to smile? I cannot smile when I am talking to him.

Mr. ARENS: I put it to you as a fact, and ask you to affirm or deny the fact, that your Communist Party name was “John Thomas.”

Mr. ROBESON: I invoke the Fifth Amendment. This is really ridiculous.

Mr. ARENS: Now, tell this Committee whether or not you know Nathan Gregory Silvermaster.

Mr. SCHERER: Mr. Chairman, this is not a laughing matter.

Mr. ROBESON: It is a laughing matter to me, this is really complete nonsense.

Mr. ARENS: Have you ever known Nathan Gregory Silvermaster?

(The witness consulted with his counsel.)

Mr. ROBESON: I invoke the Fifth Amendment.

Mr. ARENS: Do you honestly apprehend that if you told whether you know Nathan Gregory Silvermaster you would be supplying information that could be used against you in a criminal proceeding?

Mr. ROBESON: I have not the slightest idea what you are talking about. I invoke the Fifth—

Mr. ARENS: I suggest, Mr. Chairman, that the witness be directed to answer that question.

THE CHAIRMAN: You are directed to answer the question.

Mr. ROBESON: I invoke the Fifth.

Mr. SCHERER: The witness talks very loud when he makes a speech, but when he invokes the Fifth Amendment I cannot hear him.

Mr. ROBESON: I invoked the Fifth Amendment very loudly. You know I am an actor, and I have medals for diction.

. . . .

Mr. ROBESON: Oh, gentlemen, I thought I was here about some passports.

Mr. ARENS: We will get into that in just a few moments.

Mr. ROBESON: This is complete nonsense.

. . . .

THE CHAIRMAN: This is legal. This is not only legal but usual. By a unanimous vote, this Committee has been instructed to perform this very distasteful task.

Mr. ROBESON: To whom am I talking?

THE CHAIRMAN: You are speaking to the Chairman of this Committee.

Mr. ROBESON: Mr. Walter?

THE CHAIRMAN: Yes.

Mr. ROBESON: The Pennsylvania Walter?

THE CHAIRMAN: That is right.

Mr. ROBESON: Representative of the steelworkers?

THE CHAIRMAN: That is right.

Mr. ROBESON: Of the coal-mining workers and not United States Steel, by any chance? A great patriot.

THE CHAIRMAN: That is right.

Mr. ROBESON: You are the author of all of the bills that are going to keep all kinds of decent people out of the country.

THE CHAIRMAN: No, only your kind.

Mr. ROBESON: Colored people like myself, from the West Indies and all kinds. And just the Teutonic Anglo-Saxon stock that you would let come in.

THE CHAIRMAN: We are trying to make it easier to get rid of your kind, too.

Mr. ROBESON: You do not want any colored people to come in?

THE CHAIRMAN: Proceed. . . .

Mr. ROBESON: Could I say that the reason that I am here today, you know, from the mouth of the State Department itself, is: I should not be allowed to travel because I have struggled for years for the independence of the colonial peoples of Africa. For many years I have so labored and I can say modestly that my name is very much honored all over Africa, in my struggles for their independence. That is the kind of independence like Sukarno got in Indonesia. Unless we are double-talking, then these efforts in the interest of Africa would be in the same context. The other reason that I am here today, again from the State Department and from the court record of the court of appeals, is that when I am abroad I speak out against the injustices against the Negro people of this land. I sent a message to the Bandung Conference and so forth. That is why I am here. This is the basis, and I am not being tried for whether I am a Communist, I am being tried for fighting for the rights of my people, who are still second-class citizens in this United States of America. My mother was born in your state, Mr. Walter, and my mother was a Quaker, and my ancestors in the time of Washington baked bread for George Washington’s troops when they crossed the Delaware, and my own father was a slave. I stand here struggling for the rights of my people to be full citizens in this country. And they are not. They are not in Mississippi. And they are not in Montgomery, Alabama. And they are not in Washington. They are nowhere, and that is why I am here today. You want to shut up every Negro who has the courage to stand up and fight for the rights of his people, for the rights of workers, and I have been on many a picket line for the steelworkers too. And that is why I am here today. . . .

Mr. ARENS: Did you make a trip to Europe in 1949 and to the Soviet Union?

Mr. ROBESON: Yes, I made a trip. To England. And I sang.

Mr. ARENS: Where did you go?

Mr. ROBESON: I went first to England, where I was with the Philadelphia Orchestra, one of two American groups which was invited to England. I did a long concert tour in England and Denmark and Sweden, and I also sang for the Soviet people, one of the finest musical audiences in the world. Will you read what the Porgy and Bess people said? They never heard such applause in their lives. One of the most musical peoples in the world, and the great composers and great musicians, very cultured people, and Tolstoy, and—

THE CHAIRMAN: We know all of that.

Mr. ROBESON: They have helped our culture and we can learn a lot.

Mr. ARENS: Did you go to Paris on that trip?

Mr. ROBESON: I went to Paris.

Mr. ARENS: And while you were in Paris, did you tell an audience there that the American Negro would never go to war against the Soviet government?

Mr. ROBESON: May I say that is slightly out of context? May I explain to you what I did say? I remember the speech very well, and the night before, in London, and do not take the newspaper, take me: I made the speech, gentlemen, Mr. So-and-So. It happened that the night before, in London, before I went to Paris . . . and will you please listen?

Mr. ARENS: We are listening.

Mr. ROBESON: Two thousand students from various parts of the colonial world, students who since then have become very important in their governments, in places like Indonesia and India, and in many parts of Africa, two thousand students asked me and Mr. [Dr. Y. M.] Dadoo, a leader of the Indian people in South Africa, when we addressed this conference, and remember I was speaking to a peace conference, they asked me and Mr. Dadoo to say there that they were struggling for peace, that they did not want war against anybody. Two thousand students who came from populations that would range to six or seven hundred million people.

Mr. KEARNEY: Do you know anybody who wants war?

Mr. ROBESON: They asked me to say in their name that they did not want war. That is what I said. No part of my speech made in Paris says fifteen million American Negroes would do anything. I said it was my feeling that the American people would struggle for peace, and that has since been underscored by the President of these United States. Now, in passing, I said—

Mr. KEARNEY: Do you know of any people who want war?

Mr. ROBESON: Listen to me. I said it was unthinkable to me that any people would take up arms, in the name of an Eastland, to go against anybody. Gentlemen, I still say that. This United States Government should go down to Mississippi and protect my people. That is what should happen.

THE CHAIRMAN: Did you say what was attributed to you?

Mr. ROBESON: I did not say it in that context.

Mr. ARENS: I lay before you a document containing an article, “I Am Looking for Full Freedom,” by Paul Robeson, in a publication called the Worker, dated July 3, 1949.

At the Paris Conference I said it was unthinkable that the Negro people of America or elsewhere in the world could be drawn into war with the Soviet Union.

Mr. ROBESON: Is that saying the Negro people would do anything? I said it is unthinkable. I did not say that there [in Paris]: I said that in the Worker.

Mr. ARENS:

I repeat it with hundredfold emphasis: they will not.

Did you say that?

Mr. ROBESON: I did not say that in Paris, I said that in America. And, gentlemen, they have not yet done so, and it is quite clear that no Americans, no people in the world probably, are going to war with the Soviet Union. So I was rather prophetic, was I not?

Mr. ARENS: On that trip to Europe, did you go to Stockholm?

Mr. ROBESON: I certainly did, and I understand that some people in the American Embassy tried to break up my concert. They were not successful.

Mr. ARENS: While you were in Stockholm, did you make a little speech?

Mr. ROBESON: I made all kinds of speeches, yes.

Mr. ARENS: Let me read you a quotation.

Mr. ROBESON: Let me listen.

Mr. ARENS: Do so, please.

Mr. ROBESON: I am a lawyer.

Mr. KEARNEY: It would be a revelation if you would listen to counsel.

Mr. ROBESON: In good company, I usually listen, but you know people wander around in such fancy places. Would you please let me read my statement at some point?

THE CHAIRMAN: We will consider your statement.

Mr. ARENS:

I do not hesitate one second to state clearly and unmistakably: I belong to the American resistance movement which fights against American imperialism, just as the resistance movement fought against Hitler.

Mr. ROBESON: Just like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman were underground railroaders, and fighting for our freedom, you bet your life.

THE CHAIRMAN: I am going to have to insist that you listen to these questions.

MR, ROBESON: I am listening.

Mr. ARENS:

If the American warmongers fancy that they could win America’s millions of Negroes for a war against those countries (i.e., the Soviet Union and the peoples‘ democracies) then they ought to understand that this will never be the case. Why should the Negroes ever fight against the only nations of the world where racial discrimination is prohibited, and where the people can live freely? Never! I can assure you, they will never fight against either the Soviet Union or the peoples’ democracies.

Did you make that statement?

Mr. ROBESON: I do not remember that. But what is perfectly clear today is that nine hundred million other colored people have told you that they will not. Four hundred million in India, and millions everywhere, have told you, precisely, that the colored people are not going to die for anybody: they are going to die for their independence. We are dealing not with fifteen million colored people, we are dealing with hundreds of millions.

Mr. KEARNEY: The witness has answered the question and he does not have to make a speech. . . .

Mr. ROBESON: In Russia I felt for the first time like a full human being. No color prejudice like in Mississippi, no color prejudice like in Washington. It was the first time I felt like a human being. Where I did not feel the pressure of color as I feel [it] in this Committee today.

Mr. SCHERER: Why do you not stay in Russia?

Mr. ROBESON: Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no Fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear? I am for peace with the Soviet Union, and I am for peace with China, and I am not for peace or friendship with the Fascist Franco, and I am not for peace with Fascist Nazi Germans. I am for peace with decent people.

Mr. SCHERER: You are here because you are promoting the Communist cause.

Mr. ROBESON: I am here because I am opposing the neo-Fascist cause which I see arising in these committees. You are like the Alien [and] Sedition Act, and Jefferson could be sitting here, and Frederick Douglass could be sitting here, and Eugene Debs could be here.

. . . .

THE CHAIRMAN: Now, what prejudice are you talking about? You were graduated from Rutgers and you were graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. I remember seeing you play football at Lehigh.

Mr. ROBESON: We beat Lehigh.

THE CHAIRMAN: And we had a lot of trouble with you.

Mr. ROBESON: That is right. DeWysocki was playing in my team.

THE CHAIRMAN: There was no prejudice against you. Why did you not send your son to Rutgers?

Mr. ROBESON: Just a moment. This is something that I challenge very deeply, and very sincerely: that the success of a few Negroes, including myself or Jackie Robinson can make up—and here is a study from Columbia University—for seven hundred dollars a year for thousands of Negro families in the South. My father was a slave, and I have cousins who are sharecroppers, and I do not see my success in terms of myself. That is the reason my own success has not meant what it should mean: I have sacrificed literally hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars for what I believe in.

Mr. ARENS: While you were in Moscow, did you make a speech lauding Stalin?

Mr. ROBESON: I do not know.

Mr. ARENS: Did you say, in effect, that Stalin was a great man, and Stalin had done much for the Russian people, for all of the nations of the world, for all working people of the earth? Did you say something to that effect about Stalin when you were in Moscow?

Mr. ROBESON: I cannot remember.

Mr. ARENS: Do you have a recollection of praising Stalin?

Mr. ROBESON: I said a lot about Soviet people, fighting for the peoples of the earth.

Mr. ARENS: Did you praise Stalin?

Mr. ROBESON: I do not remember.

Mr. ARENS: Have you recently changed your mind about Stalin?

Mr. ROBESON: Whatever has happened to Stalin, gentlemen, is a question for the Soviet Union, and I would not argue with a representative of the people who, in building America, wasted sixty to a hundred million lives of my people, black people drawn from Africa on the plantations. You are responsible, and your forebears, for sixty million to one hundred million black people dying in the slave ships and on the plantations, and don’t ask me about anybody, please.

Mr. ARENS: I am glad you called our attention to that slave problem. While you were in Soviet Russia, did you ask them there to show you the slave labor camps?

THE CHAIRMAN: You have been so greatly interested in slaves, I should think that you would want to see that.

Mr. ROBESON: The slaves I see are still in a kind of semiserfdom. I am interested in the place I am, and in the country that can do something about it. As far as I know, about the slave camps, they were Fascist prisoners who had murdered millions of the Jewish people, and who would have wiped out millions of the Negro people, could they have gotten a hold of them. That is all I know about that.

Mr. ARENS: Tell us whether or not you have changed your opinion in the recent past about Stalin.

Mr. ROBESON: I have told you, mister, that I would not discuss anything with the people who have murdered sixty million of my people, and I will not discuss Stalin with you.

Mr. ARENS: You would not, of course, discuss with us the slave labor camps in Soviet Russia.

Mr. ROBESON: I will discuss Stalin when I may be among the Russian people some day, singing for them, I will discuss it there. It is their problem.

. . . .

Mr. ARENS: Now I would invite your attention, if you please, to the Daily Worker of June 29, 1949, with reference to a get-together with you and Ben Davis. Do you know Ben Davis?

Mr. ROBESON: One of my dearest friends, one of the finest Americans you can imagine, born of a fine family, who went to Amherst and was a great man.

THE CHAIRMAN: The answer is yes?

Mr. ROBESON: Nothing could make me prouder than to know him.

THE CHAIRMAN: That answers the question.

Mr. ARENS: Did I understand you to laud his patriotism?

Mr. ROBESON: I say that he is as patriotic an American as there can be, and you gentlemen belong with the Alien and Sedition Acts, and you are the nonpatriots, and you are the un-Americans, and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves.

THE CHAIRMAN: Just a minute, the hearing is now adjourned.

Mr. ROBESON: I should think it would be.

THE CHAIRMAN: I have endured all of this that I can.

Mr. ROBESON: Can I read my statement?

THE CHAIRMAN: No, you cannot read it. The meeting is adjourned.

Mr. ROBESON: I think it should be, and you should adjourn this forever, that is what I would say. . . .

Source: Congress, House, Committee on Un-American Activities, Investigation of the Unauthorized Use of U.S. Passports, 84th Congress, Part 3, June 12, 1956; in Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968, Eric Bentley, ed. (New York: Viking Press, 1971), 770.

***

Paul Robeson's Unread Statement before the House Committee on Un-American Activities

It is a sad and bitter commentary on the state of civil liberties in America that the very forces of reaction, typified by Representative Francis Walter and his Senate counterparts, who have denied me access to the lecture podium, the concert hall, the opera house, and the dramatic stage, now haul me before a committee of inquisition in order to hear what I have to say. It is obvious that those who are trying to gag me here and abroad will scarcely grant me the freedom to express myself fully in a hearing controlled by them.

It would be more fitting for me to question Walter, [James] Eastland and (John Foster] Dulles than for them to question me, for it is they who should be called to account for their conduct, not I. Why does Waiter not investigate the truly "un-American" activities of Eastland and his gang, to whom the Constitution is a scrap of paper when invoked by the Negro people and to whom defiance of the Supreme Court is a racial duty? And how can Eastland pretend concern over the internal security of our country while he supports the most brutal assaults on fifteen million Americans by the White Citizens' Councils and the Ku Klux Klan? When will Dulles explain his reckless irresponsible "brink of war" policy by which the world might have been destroyed?

And specifically, why is Dulles afraid to let me have a passport, to let me travel abroad to sing, to act, to speak my mind? This question had been partially answered by State Department lawyers who have asserted in court that the State Department claims the right to deny me a passport because of what they called my "recognized status as a spokesman for large sections of Negro Americans" and because I have "been for years extremely active in behalf of independence of colonial peoples of Africa." The State Department has also based its denial of a passport to me on the fact that I sent a message of greeting to the Bandung Conference, convened by [Jawaharwal] Nehru, Sukarno, and other great leaders of the colored people of the world. Principally, however, Dulles objects to speeches I have made abroad against the oppression suffered by my people in the United States.

I am proud that those statements can be made about me. It is my firm intention to continue to speak out against injustices to the Negro people, and I shall continue to do all within my power in behalf of independence of colonial peoples of Africa. It is for Dulles to explain why a Negro who opposes colonialism and supports the aspirations of Negro Americans should for those reasons be denied a passport.

My fight for a passport is a struggle for freedom—freedom to travel, freedom to earn a livelihood, freedom to speak, freedom to express myself artistically and culturally. I have been denied these freedoms because Dulles, Eastland, Walter, and their ilk oppose my views on colonial liberation, my resistance to oppression of Negro Americans, and my burning desire for peace with all nations. But these are views which I shall proclaim whenever given the opportunity, whether before this committee or any other body.

President [Dwight D.] Eisenhower has strongly urged the desirability of international cultural exchanges. I agree with him. The American people would welcome artistic performances by the great singers, actors, ballet troupes, opera companies, symphony orchestras and virtuosos of South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia, including the folk and classic art of African peoples, the ancient culture of China, as well as the artistic works of the western world. I hope the day will come soon when Walter will consent to lowering the cruel bars which deny the American people the right to witness performances of many great foreign artists. It is certainly high time for him to drop the ridiculous "Keystone Kop" antics of fingerprinting distinguished visitors.

I find no such restrictions placed upon me abroad as Walter has had placed upon foreign artists whose performances the American people wish to see and hear. I have been invited to perform all over the world, and only the arbitrary denial of a passport has prevented realization of this particular aspect of the cultural exchange which the President favors.

I have been invited by Leslie Linder Productions to play the tide role in a production of Othello in England. British actors' Equity Association has unanimously approved of my appearance and performance in England.

I have been invited by Workers' Music Association Ltd. to make a concert tour of England under its auspices. The invitation was signed by all of the vice-presidents, including Benjamin Britten, and was seconded by a personal invitation of R. Vaughan Williams.

I have been invited by Adam Holender, impresario, to make a concert tour of Israel, and he has tendered to me a proposed contract for that purpose.

Mosfilm, a Soviet moving-picture producing company, has invited me to play the title role in a film version of Othello, assuring me "of the tremendous artistic joy which association with your wonderful talent will bring us."

The British Electrical Trades Union requested me to attend their annual policy conference, recalling my attendance at a similar conference held in 1949 at which, they wrote me, "you sang and spoke so movingly."

The British Workers' Sports Association, erroneously crediting a false report that I would be permitted to travel, wrote me, "We view the news with very great happiness." They invited me "to sing to our members in London, Glasgow, Manchester or Cardiff, or all four, under the auspices of our International Fund, and on a financial basis favorable to yourself, and to be mutually agreed." They suggested a choice of three different halls in London, seating, respectively, 3,000, 4,500, and 7,000.

The Australian Peace Council invited me to make a combined "singing and peace tour" of the dominion.

I have received an invitation from the Education Committee of the London Cooperative Society to sing at concerts in London under their auspices.

A Swedish youth organization called "Democratic Youth" has invited me to visit Sweden "to give some concerts here, to get to know our culture and our people." The letter of invitation added, "Your appearance here would be greeted with the greatest interest and pleasure, and a tour in Sweden can be arranged either by us or by our organization in cooperation with others, or by any of our cultural societies or artist's bureaus, whichever you may prefer."

I have an invitation from the South Wales Miners to sing at the Miners' Singing Festival on October 6, 1956, and in a series of concerts in the mining valley thereafter.

In Manchester, England, a group of people called the "Let Paul Robeson Sing Committee" has asked me to give a concert at the Free Trade Hall in that city either preceding or following my engagement in Wales.

I have been requested by the Artistic and Literary Director of the Agence Litteraire et Artistique Parisienne pour les Echanges Culturels to sign a contract with the great French concert organizer, M. Marcel de Valmalette, to sing in a series of concerts at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris.

There is no doubt that the governments of those countries and many others where I would be invited to sing if I could travel abroad would have no fear of what I might sing or say while there, whether such governments be allies and friends of America or neutrals or those others whose friendship for the American people is obstructed by Dulles and Walter and like-minded reactionaries.

My travels abroad to sing and act and speak cannot possibly harm the American people. In the past I have won friends for the real America among the millions before whom I have performed—not for Walter, not for Dulles, not for Eastland, not for the racists who disgrace our country's name—but friends for the American Negro, our workers, our farmers, our artists.

By continuing the struggle at home and abroad for peace and friendship with all of the world's people, for an end to colonialism, for full citizenship for Negro Americans, for a world in which art and culture may abound, I intend to continue to win friends for the best in American life.

From Voices of A People's History, edited by Zinn and Arnove

Comentarios